First published in 1964, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s It’s Hard to Be a God remains one of the bleakest and most philosophically loaded works in Soviet science fiction.

The novel follows Anton, an Earth historian who is part of a team of researchers that has traveled to an unspecified planet to observe its human population and societal development. Anton quickly understands that revolutions don’t break cycles of oppression; they just restart them with new players.

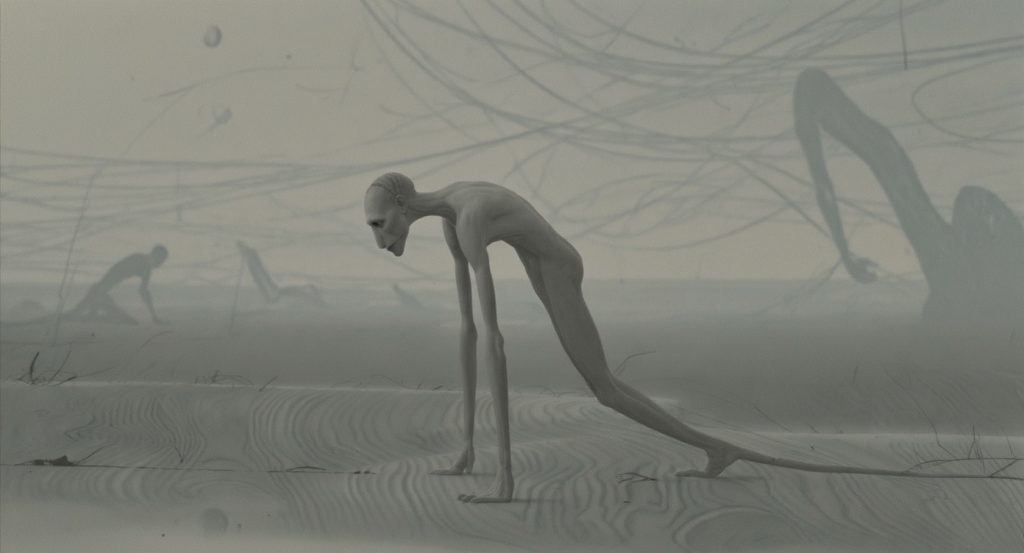

Disguised as Don Rumata, Anton is embedded in the kingdom of Arkanar, a feudal world mired in its own Dark Ages. Coming from a technologically advanced society, Anton has both the perspective and the power to change everything,but his mission demands strict non-interference. He is condemned to watch as the beginnings of a Renaissance are smothered by reactionary violence.

The tragedy of the book is not that Anton is powerless, but that he must choose to remain powerless. He has godlike advantages, but the ethical code of his world forbids intervention, forcing him into the role of a spectator while scholars are burned, artists tortured, and culture itself extinguished. The Strugatskys stage a ruthless meditation on progress: who drives it, who resists it, and why no civilization can be forced into enlightenment from above.

At the center of the struggle stand two opposing forces:

The Grays, a bureaucratic tyranny of mediocrity, who consolidate power by purging knowledge, not simply by burning books and murdering thinkers, but by hollowing out culture until nothing threatening remains. No one dares rise against them but solitary fighters like Arata the Beautiful, the revolutionary whose charisma and conviction make him less of a man but rather an unkillable symbol.

THE REAL CRUELTY OF ARATA’S ARC IS HIS SISYPHEAN CYCLE OF REBELLION, WHICH INEVITABLY CURDLES INTO THE SAME TYRANNY IT SOUGHT TO DESTROY.

And yet he presses forward, unable to abandon the belief that his cause, though doomed, must still be carried out.

The Grays thrive on the destruction of everything beautiful and elevated, revolutions mutate into the tyrants they replace, and even meager progress suffers endless cycles of perfidy, depravity, and violence.

What is left to do, then, for the few who are able to withstand the pull of the Gray ideology, those who carry the spirit but inevitably lack the conviction of the opportunists, the cruel, and the criminal? Are they victims?Bystanders? Or, because of inaction, enablers of the very Gray they despise?

And yet, the Strugatskys’ harshest judgment is reserved for the most potent collaborators of oppression: the masses. In their myopic drive for self-preservation, they become the willing tools of tyrants. Their guilt is unambiguous. Without them, no dictator can survive, and no revolution can succeed. They are key to society’s enlightenment, but their pettiness drags Arkanar into misery and regress.

Anton can be a god, but it is hard to be a god to that which you abhor.

The most devastating indictments come directly from the novel itself:

‘When the cruel among the strong are punished, their place will be taken by the strong among the weak. Equally cruel.’

‘…because then Arata was young, had not yet learned to hate, and believed that freedom alone was sufficient to transform a slave into a god…’

‘Arata was a professional rebel, an avenger by God’s grace, a rather rarely encountered figure during the Middle Ages. Sometimes historical evolution gives birth to such pike and releases them into the social currents, so that the fat carp that devour the plankton at the bottom do not slumber…’

‘And there will always be kings, more or less cruel, barons, more or less savage, and there will always be common people who will feel admiration for their oppressors and hatred for their liberator.

And only because the slave understands his master much better, even the cruelest one, than he understands his liberator, because every slave perfectly imagines himself in the place of the master, but few imagine themselves in the place of the selfless liberator.’

‘In darkness we are enslaved to ghosts.

But I fear twilight most of all, because in twilight everyone becomes equally gray.’

‘Are these people or are they not people? What is human in them? Some slaughter them right in the street, others sit in their houses and submissively wait their turn. And each thinks: whoever they want, just don’t touch me. Cold-blooded cruelty of those who slaughter, and cold-blooded submission of those who are slaughtered.’

‘The most terrible thing here is the cold-bloodedness. Ten people stand frozen with terror and submissively wait. And one comes, chooses his victim and cold-bloodedly slaughters her. The souls of these people are full of filth, and every hour of submissive waiting defiles them more and more. And now in these cowering houses, scoundrels, informers, murderers are invisibly being born—thousands of people, shackled by fear for their entire lives, will mercilessly teach fear to their children and their children’s children.’’

‘The city slept, or pretended to sleep. Did its inhabitants sense that something terrible hung over them? Two hundred thousand men and women. Two hundred thousand blacksmiths, armorers, butchers, haberdashers, goldsmiths, housekeepers, prostitutes, monks, money-changers, soldiers, vagrants, surviving scribes now tossed and turned in their stuffy beds reeking of wood shavings: sleeping, making love, calculating profits in their minds, weeping, grinding their teeth from malice or from hurt… Two hundred thousand souls!

To the stranger from Earth, there was something common among them. Surely it was that all of them, without exception, were not yet human beings in the modern sense of the word, but semi-finished products, ingots from which only the bloody centuries might someday forge the true, proud and free human being.

They were passive, greedy, and incredibly, fantastically selfish. Psychologically, almost all of them were slaves—slaves to faith, slaves to their own kind, slaves to petty passions, slaves to self-interest. And if by the force of fate one of them was born or became a master, he did not know what to do with his freedom. He would again hasten to become a slave—a slave to wealth, a slave to unnatural excesses, a slave to corrupt friends, a slave to his own slaves.

The greater part of them bore no guilt. They were too passive and too ignorant. Their slavery was built upon passivity and ignorance, while passivity and ignorance constantly gave birth to slavery.’

‘It’s hard to be a god,” Rumata thought to himself.

He said patiently:

“You won’t understand me. I’ve tried twenty times to explain to you that I’m not a god, but you didn’t believe me. And you won’t believe why I can’t help you with weapons…”

“Do you have lightning?”

“I cannot give you lightning.”

“I’ve heard that twenty times already,” said Arata. “Now I want to know why!” “I repeat to you: you won’t understand.”

“Try to explain it to me.”

“What do you intend to do with lightning?”

“I’ll burn this gilded scum like wood shavings, every last one of them. Their entire damned race to the twelfth generation. I’ll wipe their fortresses from the face of the earth. I’ll burn their armies and everyone who protects or supports them. You needn’t worry, your lightning will serve only good, and when only liberated slaves remain on earth and peace comes, I’ll return the lightning to you and never ask for it again.”

Arata fell silent and again reached for the bread. Rumata watched his fingers, left without nails. Two years ago don Reba himself had torn out his nails with a special device.

You don’t know everything yet, Rumata thought to himself.You still console yourself with the thought that only you are doomed to defeat. You don’t yet know how hopeless your cause is. You don’t yet know that the enemy is not so much outside your soldiers as within them. You may perhaps overthrow the Order and the wave of peasant rebellion will cast you onto the Arkanar throne, you will raze the noble castles to the ground, you will drown the barons in the Strait, and the risen people will pay you all honors as a great liberator, and you will be good and wise—the only good and wise man in your kingdom. And out of goodness you will begin to distribute land to your comrades-in-arms. But what do your comrades need land for without serf peasants? And the wheel will turn in the opposite direction. And it will be well if you manage to die a natural death and not see how new counts and barons emerge from your yesterday’s faithful warriors. This has happened before, my glorious Arata, both on Earth and on your planet.’

‘Rumata felt a strange sensation of painful duality. He knew he was right. And yet this rightness somehow humiliated him before Arata. Arata clearly surpassed him in something, and not only him, but all those who had come uninvited to this planet and, filled with powerless pity, observed the terrible ferment of its life from the rarefied heights of dispassionate hypotheses and alien morality.

And for the first time Rumata thought: nothing can be gained without something being lost—we are infinitely stronger than Arata in our realm of good. And infinitely weaker than Arata in his realm of evil…’

→ For completists, obsessives, and people with too many tabs open.

Go root around in the archive. It’s messy, but so is life: themaladapted.substack.com